The topic of languages at Eurovision is always an interesting one. Every year, when the latest entries are revealed, there is always a lot of buzz and speculation: who will opt for a ballad? Who will send the novelty act? And importantly: who will perform in their own national language?

Years ago, Eurovision used to feature languages from every nation across Europe – from Turkish ballads to Swedish bops, but lately the Eurovision Song Contest has been criticised for the dominance of English-language songs(1)(2), arguably diminishing its cultural importance.

But after a wait of ten years, 2017 saw the contest won by a non-English song once again. This was followed by not one, but TWO, winning entries not featuring English within the five years that followed; we had our third-ever Italian-language winner in 2021, followed by our second-ever winning entry featuring Ukrainian.

UPDATED: I was first inspired to write this analysis in the year following Portugal’s win, but I have since updated this article on a yearly basis, most recently in April 2024.

Read more: National Languages at the Eurovision Song Contest 2024

Are there language rules in Eurovision?

Simply put: no. There is currently no rule stating which language (or languages) a country can perform in at Eurovision. However, there once were.

From 1966-1972 and again from 1977-1999, entrants were required to sing in one of the country’s official languages. Before this, it’s safe to say that no-one had really considered singing in a language that wasn’t their own; in fact Sweden was the first to do so in 1965, singing in English.

From 1999, all countries have been free to sing in whichever language they choose (including invented languages). However, it wasn’t until 2007 that a country opted to sing in neither their national language nor English (Cyprus entered a song in French, while Latvia sang in Italian) – and this has only happened a handful of times since (most recently when Austria entered a song completely in French in 2016).

ABBA won Eurovision in 1974, after the rule on language had been dropped. It was later reinstated.

Why do so many countries sing in English at Eurovision?

The answer to this is less straight forward; there are a lot of reasons many countries shun their national languages in favour of English.

- English-language songs win more often. In fact, since the language rule was dropped in 1999, only four winning songs have not included English – Serbia in 2007, Portugal in 2017, Italy in 2022 and Ukraine in 2023. (Although both of Ukraine’s previous winning entries were partly sung in another language: Ukrainian in 2004 and Crimean Tatar in 2016).

- English is understood by a large number of viewers. Though this is also true of many languages when looking at native speakers (particularly German or Russian) the sheer number of people across Europe who can understand English or are at least used to hearing English songs on the radio is pretty huge.

- English is seen as a ‘neutral’ language. This may be a huge generalisation, but in many countries, the second language taught in schools during the time of communism was Russian or German, whereas for many people, English had no political connotations and so was seen as being a sign of neutrality, European integration and even modernity.

- Many performers are looking to forge international careers. This is particularly true of ‘Eastern Bloc’ countries, where performers tend to be very successful in their own right. Belarus’ entrant for 2018, for example, was a bit of a celeb in his homeland of Ukraine and other former Soviet countries like Russia and Armenia, where he’s already topped the charts. For him, Eurovision could have been his big break onto the international stage, so his choice to translate his entry from Russian into English wasn’t all that surprising. Similarly, Dima Bilan – Russia’s only winner to date – released his first English-language album the year after his 2008 win.

Are English-language songs taking over Eurovision?

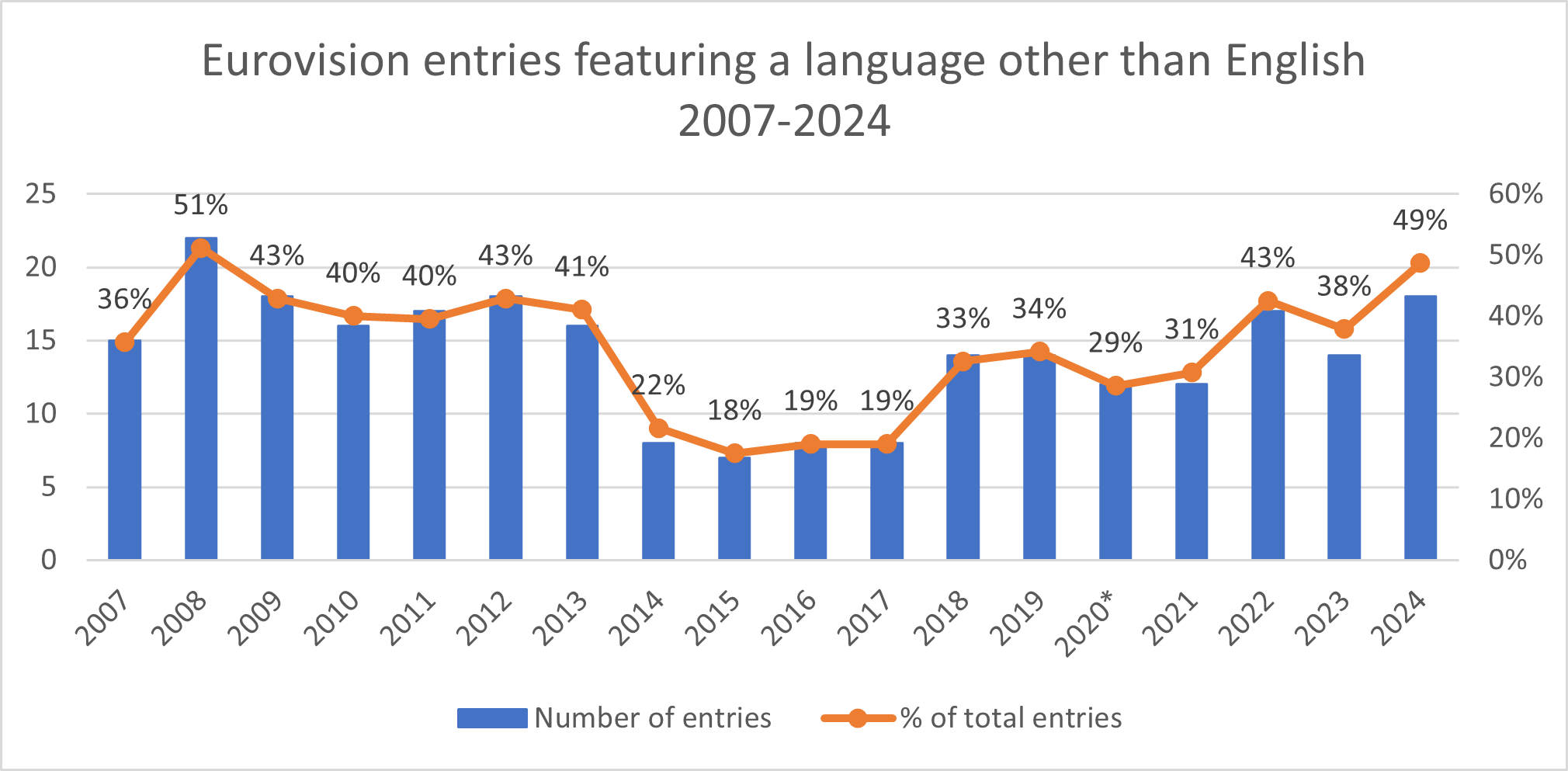

Yes and no. We can see that in the mid-2010s, the number of entries featuring national languages reached one of its lowest rates ever. But since then, we can see that the number of national languages present on the Eurovision has seen a steady resurgance. In fact, in 2024, almost half of the entries (18 out of 37) feature a language other than English.

As you can see in the graph above, the year after Serbia’s win in 2007 saw more than half of entries in a language other than English. A similar peak occurred after Portugal’s win in 2017, but this was still not as high as the level pre-2013.

Another increase can be seen in 2022, after Italy’s victory, with the proportion and quantity of native language entries reaching a 10-year high. It’s hard to judge what has led to another peak in 2024, but it’s safe to say that Käärijä’s resounding success in the televote in Liverpool must have helped.

And of course: English at Eurovision is a relatively recent phenomenon (part in thanks to the Eurovision language rules outlined above). As you can see from this excellent video below, French was actually the most commonly-used language at Eurovision well into 1999.

Eurovision in the 2010s: Why did more countries start singing in English at Eurovision?

It’s impossible to pinpoint the exact reason, but several countries who could always be ‘relied’ on to sing in their national tongue suddenly started sending entries in English at around the same time.

Israel, for example, had always sung at least partly in Hebrew until 2015. The country’s first ever entirely-English entry was also their most successful in almost a decade, prompting them to continue to send English-language entries ever since. (Although it is worth nothing that their 2020 entry included four languages: English, Hebrew, Arabic and Amharic.)

Similarly, Balkan nations Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro and Macedonia regularly performed songs in their respective languages between 2008-2013 but largely switched to English in the years following. More recently, Hungary has withdrawn from the competition. The Central European nation had a strong track record of singing in their national languages.

Who always sings in their national language at Eurovision?

Luckily, there are a handful of countries who always perform in their national language at Eurovision.

France and Italy have always sung at least partly in one of their national languages (including Neapolitan, Corsican and Breton). This claim is also shared by Luxembourg, Andorra, Monaco and Morocco – none of whom are current regulars at the contest – in addition to both Yugoslavia and Serbia and Montenegro, neither of which exist anymore.

Spain and Portugal have also always entered in Spanish and Portuguese respectively, bar one year. Spain entered in English in 2016, while Portugal did the same in 2021, breaking the hearts of Eurofans everywhere in the process. Luckily, they have returned to Portuguese in 2022.

Of course, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and Malta have also always sung in a national language, which (luckily for them) includes English.

Portugal’s Salvador Sobral | Image courtesy of Radio NZ

How is voting affected by languages in Eurovision?

The answer to this one is not so simple, but still interesting.

Languages and recent winners

Firstly, let’s look at Portugal’s victory in 2017. Anyone who watched the show will remember that Salvador Sobral swept up jury points from across the continent, receiving 12 points from 18 different countries (Armenia, Poland, Sweden, and Israel to name just a few), with points from televote coming from an equally wide range of countries. We can assume here that language played no real part in Salvador’s win: Portuguese is not a language that is widely spoken in Europe and whilst it is a Romance language, fellow Romance-speaking country Italy gave Salvador the lowest points of all countries, suggesting a closer understanding didn’t necessarily help.

Similarly in 2021, Italy’s Maneskin stormed to victory thanks to their commanding lead in the televote, where they picked up the maximum 12 points from a diverse range of countries: Bulgaria, Malta, San Marino, Serbia and Ukraine. Of these five countries, only Malta and San Marino would boast a strong knowledge of Italian amongst their voting base. Although neighbours Slovenia and Croatia also gifted Italy 12 jury points (along with Georgia and Ukraine), I think it is safe to say that language was not the strongest influencing factor here.

Of course, it would be very misguided to suggest that Ukraine’s decisive victory in 2022 was influenced by language when there were so many things happening across the continent at the same time. However, it is interesting to note that language does not seem to have been a hindering factor for the country; without Russia and Belarus participating, Ukraine was the only East-Slavic-speaking country participating.

Languages at Eurovision: Serbia’s 2007 win

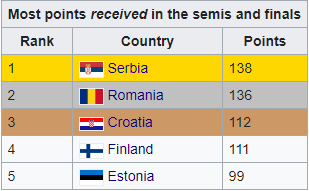

However, when you look to Serbia’s win in 2007, the story is a bit different. Marija Šerifović clocked up the maximum 12 points from nine countries. These included all the nations of former Yugoslavia, of which three (Croatia, Bosnia and Montenegro) speak a language that is technically the same as Serbian, while it can be assumed many in Macedonia and Slovenia still have strong comprehension of the language.

Serbia’s Marija Šerifović performing Molitva (Prayer) in 2007 | Source: wiwibloggs.com

Additional 12 points came from Austria and Switzerland, home to a large number of former-Yugoslav emigres, as well as neighbour Hungary. Finland also gave its 12 points to Serbia. We can presume here that language did play a role in Marija’s victory, although doubtless cultural and historic reasons were present too. (It was also a bloody good song.)

The dominance of English in the 90s

Of course when looking at the relation between the language of a song and victory in the contest, you cannot ignore Ireland and the United Kingdom’s success in the 90s: Ireland won the contest four times (in 1992, 1993, 1994 and 1996) and came second twice (1990 & 1997), while the UK won once (1997) and came second three times (1992, 1993 and 1998). In the entire decade, there were only three years when the UK or Ireland did not finish in one of the top two position (and three years when they occupied both).

It doesn’t seem coincidental that since all countries were allowed to perform in English (from 1999 onwards), neither country has made it to the top two.

The 90s was a big time of change for Europe – and this was reflected in Eurovision, with plenty of former Eastern-Bloc nations debuting in this decade. And I think it would be fair to say that the use of English in Europe was definitely on the rise at this time, with huge music acts such as the Spice Girls, Take That, Oasis and Boyzone enjoying international success. In my mind it cannot be denied that these two things helped the UK and Ireland (and their English-language songs) to repeated victory in the 90s.

Of course, Malta was also performing in English during the 90s and did not share success on the same level.

Language families and connected voting

One much less obvious impact of languages on Eurovision results is that of language families. This is probably the biggest presumption I am going to make in this analysis, but if you look at the voting patterns for Hungary, you notice something a bit odd.

The countries which have given Hungary the most points in the competition (up to 2018) Source: Wikipedia

Hungary received the most votes from Serbia and Romania (home to sizeable Hungarian populations), Croatia (one of its neighbours) and then… Finland and Estonia. On the face of it, these two countries at the crossroads of Nordic and Baltic Europe seem to have little in common with Central-European Hungary… until you consider language: Finnish, Estonian and Hungarian are all Finno-Ugric (or Uralic) languages.

Hungarian, Estonian and Finnish are all part of the same language family – shown here as Uralic (olive green)

While I don’t know enough about these languages to talk about any kind of mutual intelligibility, it’s nevertheless interesting that these countries share a link when it comes to voting, which may or may not be rooted in language.

Which languages do we rarely hear at Eurovision?

Interestingly, the only country to never have entered a song in one of its national languages is Azerbaijan, who have sung solely in English since their debut in 2008. But I think it’s also worth mentioning a few other languages which are heard surprisingly rarely considering their huge cultural influence.

Countries where Russian is widely used or understood (including 9 Eurovision countries, apart from Russia)

Firstly: Russian. Whilst I did mention the perception in some countries of Russian as a language of oppression, it is a very beautiful language and one which has rich and deep cultural connections. The Russian diaspora is spread far and wide in Europe and coupled with the former Soviet states where Russian is still widely spoken, there is a huge audience for Russian-language music. And yet the language is very seldom used. Interestingly, when Moscow played host to the contest in 2009, three countries performed in Russian: Russia, Latvia and Lithuania. Happily, the 2021 contest saw the Russian language return to the Eurovision stage for the first time since 2011.

Irish has only been heard once in the contest (so far) – in 1972. However, since Ireland began participating in the Junior Eurovision Song Contest, all three of its entries have featured the Irish language. Is Ireland gearing up to bring its historic language back to the stage?

Bonnie Tyler, one of Wales’ most famous singers, performed for the UK in 2013

Despite plenty of Welsh acts having performed in the contest, Welsh has never been heard at Eurovision. Neither have Scottish Gaelic, Cornish or Manx for that matter, with the UK having sent all its entries in English. Interestingly, Wales has had its own Welsh-language song competition since 1969 when BBC Cymru were interested in sending a separate Welsh entry to Eurovision. This was not allowed, however Wales did make its debut in the Junior Eurovision Song Contest in 2018, singing only in Welsh. They came last.

Eurovision in the 2020s: is the tide turning for native languages at Eurovision?

Of course, no analysis of language trends at Eurovision would be complete without mentioning the absolute triumph that was the 2021 Contest. For the first time since 1995, no English-language song made it to the top 3. Instead, Italy won, while France and Switzerland (who both entered in French) came 2nd and 3rd respectively.

In fact, as Barbara Pravi pointed out mid-way through the Jury vote announcements, the two French-language songs were neck-and-neck to win the Jury vote, while the top two songs with the televote were sung entirely in Italian and Ukrainian.

And yet, it seemed the impact of this historic contest might prove to be short-lived. Despite the French language’s impressive showing in 2021, the language will be entirely absent at the 2022 contest – for the first time ever.

Of the top 10 entries at the 2022 contest, 70% featured a national language.

Luckily, our fears were assuaged: Ukraine triumphed in 2022 with Eurovision’s first-ever winning entry sung entirely in Ukrainian, making it the first instance since 1990/1991 where two non-English entries won back-to-back.

But better still – if we look further down the table of results, we seem something interesting.

A revival of national languages? The top 10 of Eurovision 2022

Of the top 10 entries, only Sweden (4th), Greece (8th) and Norway (10th) did not sing in their own language, meaning of the top 10 songs, 70% featured a national language. And better yet, in 11th place was the Netherlands, whose S10 sang in Dutch.

Furthermore, the top 5 songs in the televote were Ukraine, Moldova, Spain, Serbia and the UK; five entries that were sung in a native languages – the top 4 of which were non-English. Might this suggest that non-English entries are in fact becoming more popular with the public…?

Might this trend continue in 2023? Let’s keep our fingers crossed…!

Why are languages at Eurovision important?

Of course, I can’t finish this analysis/essay/blog post without turning to the question: why is language such a big deal in Eurovision? The answer is I don’t know and in a lot of ways, it needn’t be.

The original concept of Eurovision was to bring together the nations of Europe after World War II. In the early editions of the contest (and particularly when the use of language was restricted), the show came to represent a chance for nations to show off their history and culture – but this was not the founding principle of the show. And as such, one could argue that singing in a widely-understood language does more to bring people together than through 34 very different languages.

My monolingual, 65-year-old Dad voted for a song sung in Albanian in 2018 – a language he might never have heard before – and I think that’s beautiful.

However, on the other hand, Europe is very rich in different languages and cultures and by allowing one language to dominate will lead to a gradual descent into largely homogenous songs. Indeed, in the 23 years since the language rule was abolished in 1999, only 6 entries have been sung partly or entirely in a foreign language.

So why do I care so much about languages in Eurovision? Simply put, I love the idea that for one evening a year people in my hometown in the UK might listen to songs in Hungarian, Armenian or Lithuanian – languages they might never have heard before – and appreciate the song nonetheless. My monolingual 65-year-old Dad voted for a song sung in Albanian in 2018 – a language he might never have heard before – and I think that’s beautiful. There are so many beautiful, brilliant, bold songs released every year in languages across Europe and to only listen to those in your mother tongue is to deprive yourself of them.

So in conclusion: yay for bringing people together, but more yay for doing it despite language barriers.

Wow! Really enjoyed the article and the thorough research.

Thanks Sabina, glad you enjoyed. Hope you’re looking forward to the show in May!

So fascinating to read – I never knew any of this!

Glad I could impart some wisdom haha! Eurovision is a bit of a linguist’s dream – if only there were more non-English languages being represented…

this is still bothering me! I am watching the Swedish Mello right now, to see who is going to the finals in the Swedish Eurovision selection, and only one song was in Swedish. And mostlz the same boring, English pop “sigh”. As zou said one evening a year it would be nice to hear all these beautil different languages, we normally arent exposed to. Great article, well researched. Cheers

Thanks Siri! I would absolutely love to hear Swedish or Saami on the Eurovision stage representing Sweden one day, but it just seems so unlikely. Did you know Sweden were the first non-English speaking country to enter a song in English – before anyone had even thought to invent a rule about languages!